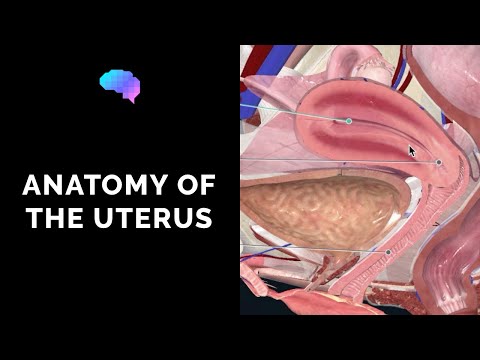

Hysterectomy is the most commonly performed gynecologic procedure. Total hysterectomy involves removal of the uterus and cervix, and it can be performed with either a transabdominal, laparoscopic, or transvaginal approach. Subtotal or partial hysterectomy involves removal of the uterus but not the cervix, and it is performed for benign causes such as fibroid uterus or dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Radical hysterectomy is performed for malignancy and involves removal of the uterus along with the cervix and ovaries and is commonly associated with lymph node dissection. Vaginal hysterectomy is the preferred surgical method for the treatment of benign uterine disease.

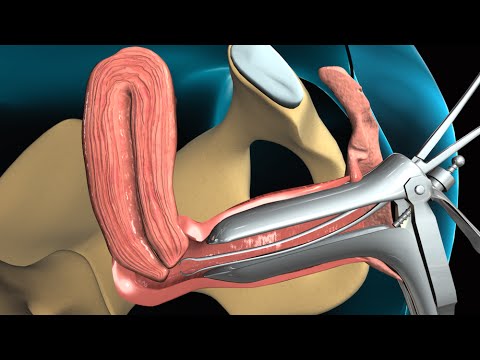

Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy is a new technique that serves as an adjunct to vaginal hysterectomy for lysis of adhesions and concomitant adnexal surgery. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy is technically more challenging and requires surgical expertise. It is indicated when vaginal hysterectomy and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy are not possible due to a narrow pubic angle, small vagina, or immobile uterus. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy is associated with long surgical times and a higher rate of complications, especially urinary tract injuries.

Once there, the catheter is used to deliver agents that block off the blood vessels that feed the uterine fibroids. Specific embolic agents include gelatin sponges, polyvinyl alcohol particles, or tris-acryl gelatin microspheres. Total radiation exposure, following this procedure is approximately 15 rads, which is comparable to that in one to two computed tomography scans or barium enemas1 . UFE is a minimally invasive technique that allows for quick recovery after the procedure. UFE does not remove uterine fibroids, but causes the fibroids to shrink about 30-50%.

Women can have improvement in both their bleeding symptoms and pressure symptoms after UFE. A pelvic MRI is performed before the procedure to determine if a woman would benefit from a UFE. Women also need to have a physical examination and discuss their medical history with an interventional radiologist to determine if they are suitable candidate for a UFE procedure. Advantages over surgery include no abdominal incisions and a shorter recovery time.

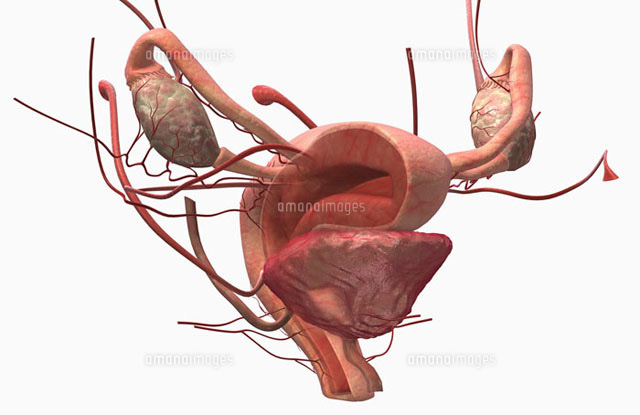

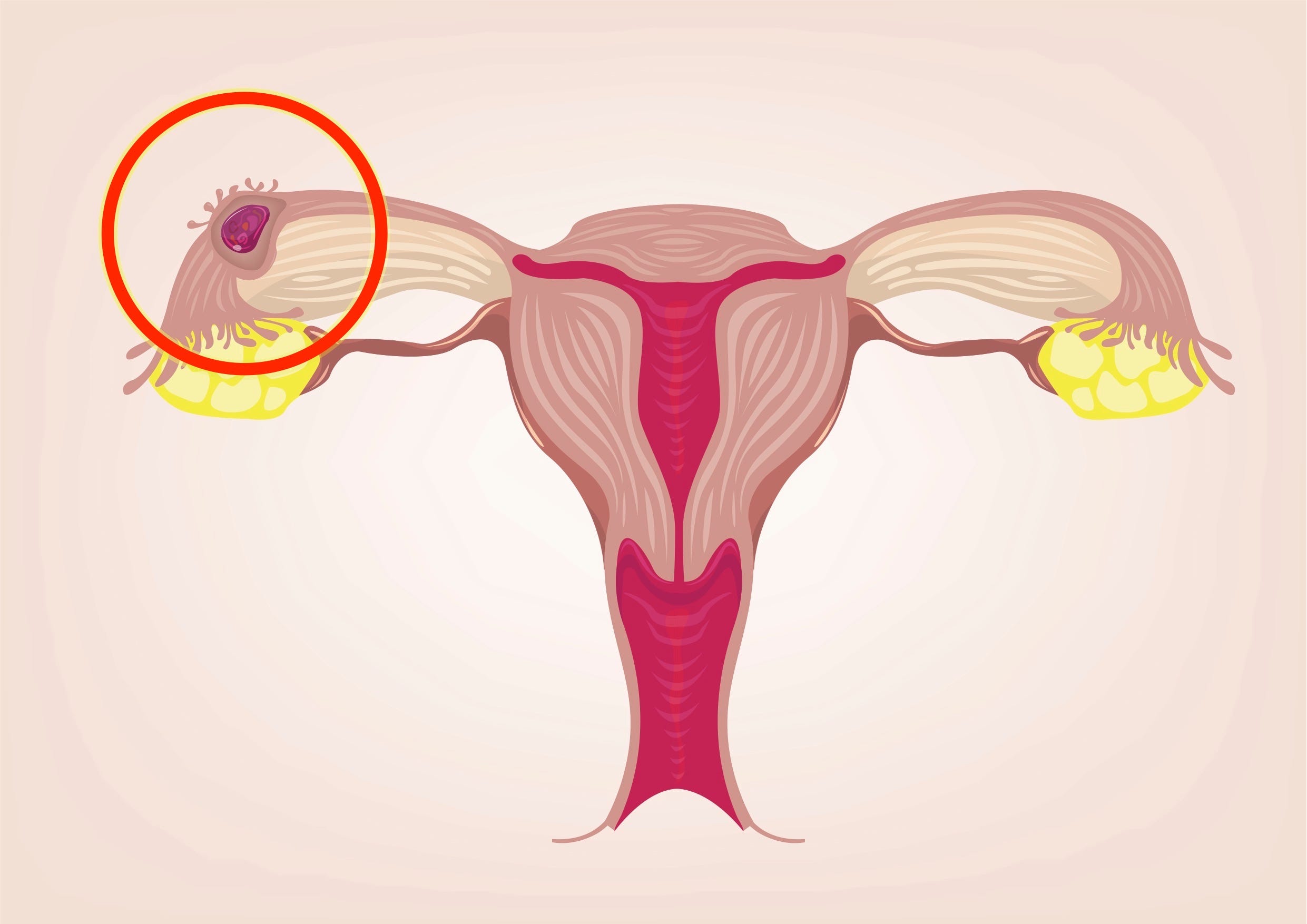

Complications may occur if the blood supply to your ovaries or other organs is compromised. The safety of these procedures in women desiring pregnancy has not been demonstrated and is generally not advised for women who want to have children in the future. Learn more about Uterine Fibroid Embolization at Brigham & Women's Hospital. As previously stated, abdominal hysterectomy is the most common source of ureteral injury inadvertently caused by a surgeon. Here, the potential for ureteral injury is greatest during the ligation and division of the uterine arteries, followed by division of the ovarian vessels and infundibulopelvic ligament . In radical hysterectomy, the ureter can be skeletonized when removing an adjacent tumor, and this can result in a lack of blood supply and delayed death of tissue.

Radical hysterectomy also may require en-bloc resection of a ureteral segment (in order to achieve a tumor-free margin). Prior irradiation can compromise ureteral blood supply, make wounds heal poorly and increase the risk of ureter injury during pelvic surgery . Fistulas from the radiated ureter are very difficult to repair and typically require two or more operations. Previous episodes of endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease can lead to dense ureteral adherence and so increase the chances for injury during surgery.

Cancers can directly invade and can fix the ureter or distort its course. Masses in the ovaries and fallopian tubes also can distort the infundibulopelvic ligament and displace the ureter. Severe pelvic prolapse also can increase the risk of ureteral injury. Infected or inflamed tissues are other important contributing factors for ureteral injury. A 14-year-old Chinese girl was admitted to our hospital more than 6 months after secondary dysmenorrhea and 6 days after B-ultrasound-diagnosed uterine malformations. She had menarche at the age of 12 years and had a normal menstrual history.

However, since January, 2010, she started to suffer from menstrual pain, which could not be alleviated until 1 week after menstruation ending. On July 25, the patient showed intensified persistent abdominal pain with anus bulge, which was slightly alleviated with an unclear treatment by the local hospital. She was then admitted to our hospital for further diagnosis and treatment. An anal examination revealed a slightly larger anteverted uterus with mild tenderness, and the bilateral adnexa were normal.

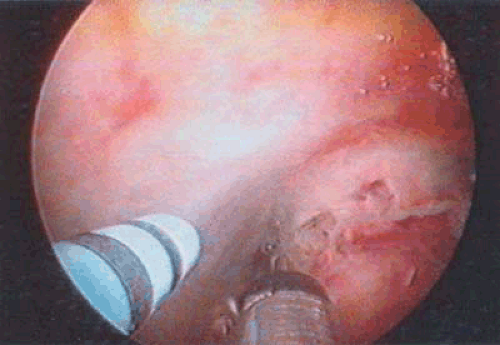

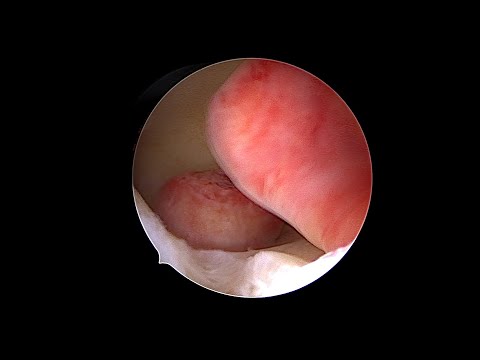

The myometrial thickness between the echoic area and the endometrium was approximately 12mm. In addition, B-ultrasound examination of her urinary tract showed normal results.B-ultrasound-guided hymen-protecting hysteroscopy and laparoscopy were performed on August 5, 2010. Misoprostol (0.4mg) was placed into her rectum at night and 3 hours before the surgery to soften her cervix. The results of hymen-protecting hysteroscopy revealed a narrow horn-shaped right-side uterine cavity.

The laparoscopy results revealed a small narrow right-side uterine cavity. However, the left side of the cavity was full without a depressed bottom, and showed an enlarged size, which was analogous to 40 days' pregnancy . Her bilateral fallopian tubes and both ovaries showed normal morphology.

Under hysteroscopy, her uterine wall blood was cleaned using uterine distention fluid . After OUS removal, her uterine cavity showed normal morphology, with both sides of horns and fallopian tube entry visible. In addition, we found that the left side of her uterine cavity became smaller and showed normal morphology.

The prevalence of urinary tract injuries is higher following radical hysterectomy than after total abdominal hysterectomy for benign indications . Bladder laceration, which is usually recognized and corrected at primary surgery, is the most common injury . Predisposing factors include distortion of the pelvic anatomy by adhesions due to previous surgeries, radiation therapy, or pelvic inflammatory disease . The stage of the underlying malignancy, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and postoperative infection are other predisposing factors for urinary tract complications . The prevalence of ureteral injuries is much higher following radical hysterectomy with lymph node dissection for pelvic malignancy than after hysterectomy for benign disease.

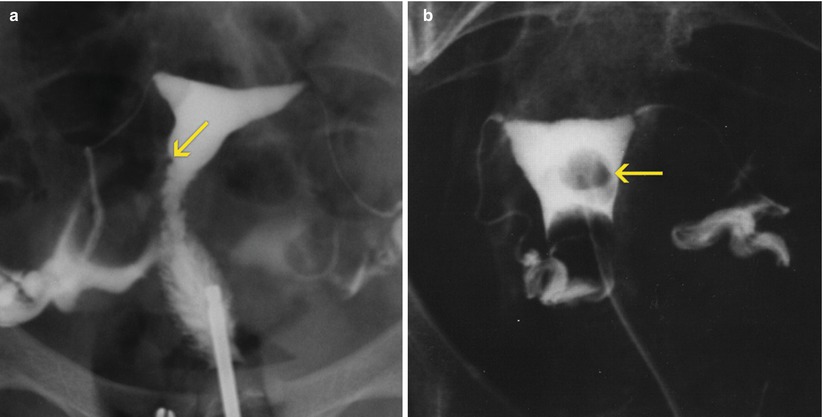

Such injuries may occur due to direct trauma during surgery or secondary to ischemia from stripping of the periureteral fascia. Bladder and ureteral injuries may heal without complications or lead to urinoma , ureteral stricture and obstruction , and ureterovaginal or vesicovaginal fistula . IVU, cystography, retrograde py-elography, CT urography, and CT cystography are the preferred imaging methods for demonstrating ureteral and bladder injuries. CT has the advantage of demonstrating other associated intraabdominal processes and is replacing IVU as the primary imaging method for evaluating ureterovesical injuries. The primary imaging sign of ureteral injury is ureteral obstruction with or without contrast material extravasation. Extraluminal extension of contrast material into the vagina confirms a ureterovaginal fistula and is better depicted with CT urography.

Conventional cystography and CT cystography have a similar sensitivity for demonstrating active urine leak due to bladder injury . A total abdominal hysterectomy means removing the uterus and the cervix. Women who have had abnormal pap smears are usually encouraged to have their cervix removed. A subtotal or supra-cervical hysterectomy means removing only the upper part of the uterus. Women who retain their cervix may have less bladder leakage and vaginal relaxation later in life; however, this has not been scientifically proven.

Women who have had a supra-cervical hysterectomy will continue to need periodic pap smears. In addition, some women will have monthly spotting or light bleeding if endometrial glands are still embedded in the cervical tissue. Most women spend three nights in the hospital and six weeks recovering at home.

Some women experience a complication that results in a longer recovery time. In most gynecologic diseases, surgery remains the treatment of choice. Hysterectomy is the second most common elective gynecologic surgery performed for both benign and malignant conditions of the uterus. Approximately 600,000 hysterectomies are performed each year in the United States . Total abdominal hysterectomy is the most common and also the most invasive type of hysterectomy. Radical hysterectomy performed for cervical and endometrial cancer involves more extensive parametrial resection and has a much higher rate of complications (2–4).

Surgery also plays an important role in both the staging and treatment of ovarian cancer. Tumor debulking involves omentectomy, extensive lymph node dissection, and resection of metastatic peritoneal implants . The various types of gynecologic surgery and their related complications are shown in Table 1.

Postsurgical complications may occur within a few days or weeks of surgery, or they may not occur for several months or even years. The imaging methods that are considered the most suitable for the detection of these complications are shown in Table 2. A fistula is defined as an abnormal communication between two epithelial surfaces resulting from an injury or disease. It connects an abscess cavity or hollow organ to the body surface or to another hollow organ. Fistulas can be early as well as delayed complications following surgery, and they can be secondary to bowel or urinary tract injury. The nature of a fistula is related to the type of malignancy or surgery and to any associated radiation therapy.

The prevalence of fistulas is higher following radical hysterectomy and radiation therapy for cervical cancer . Enterovesical fistulas involve the dome of the bladder, whereas vesicovaginal fistulas involve the posterior bladder wall. There are also reports of fistula between the uterus and bladder following cesarean section, manifesting with vaginal urine leakage, cyclic hematuria, and amenorrhea . Women with fistula between urinary and genital tracts present with dribbling of urine from the vagina, whereas those with enterovesical fistula present with pneumaturia and dysuria.

Diagnostic work-up includes conventional fluoroscopic barium studies, IVU, retrograde pyelography, and fistulography, as well as cross-sectional imaging . The appropriate imaging method depends on the anatomic location of the fistula. Cutaneous fistula to the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract is better delineated with fluoroscopic fistulography than with cross-sectional imaging.

Ureterovaginal fistulas are visualized with both IVU and CT urography. Vesicovaginal, rectovaginal, and enterovesical fistulas are well visualized at cross-sectional imaging. MR imaging is especially well suited for the diagnosis of vesicovaginal and rectovaginal fistulas owing to its superior soft-tissue contrast resolution. Axial thin-section CT scans with multiplanar reformatted images are helpful in the detection of fistulas and their morphologic features . Sentinel lymph node mapping may be used in early-stage endometrial cancer if imaging tests don't clearly show signs that cancer has spread to the lymph nodes in your pelvis.

To do this, a blue or green dye is injected into the area with the cancer, near the cervix. The surgeon then looks for the lymph nodes that turn blue or green . These lymph nodes are the ones that the cancer would first drain into . They're removed and tested to see if there are cancer cells in them.

If so, more lymph nodes are taken out because they likely have cancer cells in them, too. If there are no cancer cells in sentinel nodes, no more nodes are removed. This procedure is usually done at the same time as surgery to remove the uterus . Your doctor will talk with you about whether SLN mapping is an option for you. The uterus is surgically removed with or without other organs or tissues.

In a total hysterectomy with salpingo-oophorectomy, the uterus plus one ovary and fallopian tube are removed; or the uterus plus both ovaries and fallopian tubes are removed. In a radical hysterectomy, the uterus, cervix, both ovaries, both fallopian tubes, and nearby tissue are removed. These procedures are done using a low transverse incision or a vertical incision.

This outpatient procedure involves laparoscopic removal of the uterine body, and the patient is able to keep her cervix. The patient can either keep her ovaries or have them removed at the same time. Fallopian tubes are often removed since it is now believed that fallopian tubes are the source for epithelial cancers of the ovaries. This is a nice way to manage a large fibroid uterus without having to do a big incision.

Other conditions, such as endometriosis and adhesions, can be treated at the same time. This outpatient approach is associated with less pain, fewer adhesions, and a quicker recovery than the open approach. Fibroids that are in the wall or outer lining of the uterus can be removed either through an abdominal myomectomy or a laparoscopic approach. An abdominal myomectomy involves making an incision on the abdomen in order to access the uterus and then surgically remove the fibroids. Either a Pfannenstiel or vertical skin incision can be used to perform an abdominal myomectomy. The type of incision made depends on the size of the uterus and fibroids.

These surgical approaches use 3-5 small abdominal skin incisions that are 5-12 mm to perform the same surgery. A laparoscope, or thin long camera, is placed through an incision in the umbilicus or above the umbilicus, depending on the size of the uterus and uterine fibroids. Long instruments are then inserted through the remaining small incisions to perform the removal of the fibroids and then to repair of the uterus. Robotic myomectomies are performed using specialized equipment that allows for free range of motion and a three-dimensional high definition view of the surgical anatomy. The main treatment for endometrial cancer is surgery to take out the uterus and cervix.

When the uterus is removed through an incision in the abdomen , it's called a simple or total abdominal hysterectomy. Ureteral injuries are a potential complication of any open or endoscopic pelvic operation. Gynecologic surgery accounts for more than 50 percent of all ureteral injuries resulting from an operation, with the remaining occurring during colorectal, general, vascular and urologic surgery.

(2-4) The ureter is injured in roughly 0.5 to 2 percent of all hysterectomies and routine gynecologic pelvic operations and in 10 percent of radical hysterectomies. Of ureteral injuries from gynecologic surgery, roughly 50 percent are from radical hysterectomy, 40 percent are from abdominal hysterectomy and less than 5 percent result from vaginal hysterectomy. All gynecologic ureteral injuries occur to the distal one third of the ureter . When women wish to preserve childbearing potential, a myomectomy may be performed.

Unlike hysterectomy in which the entire uterus is removed, myomectomy is a surgical procedure in which individual fibroid are removed. Approximately 18,000 myomectomies are performed yearly in the United States. This technique is primarily useful for women with bleeding or pregnancy-related problems as there is usually little change in the size of the uterus with this approach. Certain subserosal fibroids may be removed abdominally during a procedure called laparoscopic myomectomy which involves a different instrument called a laparoscope. In general, myomectomy diminishes menorrhagia (prolonged and/or profuse menstrual flow) in roughly 80% of patients presenting with this symptom.